Resentment and empathy towards leadership

Product management is such a misunderstood role. Mainly because it’s unique per company.

But a lot of the "it's unique per company" is actually "it's unique per founder".

This post does not offer recipe-like advice of how to deal with different founder types. Its purpose is to suggest a way of thinking that I’ve found to be more practical than my previous default. A way of thinking that leans more on empathy than resentment.

I'll share experiences from my past workplaces that contributed to this mindset change. And I’ll add excerpts I’ve collected through the years from public content that resonated with me. So this is not a short read.

Let’s start.

The product-oriented founder is the first product manager. Usually, the cofounder-CEO. That person determines what product management will look like in the company. Mostly in the way they implicitly evolve the decision making culture. And also in the way they delegate and create (or don't create) autonomy for others over time.

By autonomy, I don’t mean 100% autonomy. I mean that employees feel empowered to influence and execute decisions. 100% autonomy could actually be problematic in an org as there are dependencies. Unless you are the CEO, everyone is dependent on other team’s decisions and constraints.

I like the way Brian Chesky (Airbnb CEO) talks about empowerment from the CEO’s perspective. He starts off bluntly, but adds nuance as he goes (37:52-40:57 here):

I don’t believe that the way to empower people is to give them autonomy. I tried that for 10 years. I kept trying to give people more and more autonomy. And what happened was, control is not zero-sum. There's a way where everyone can be autonomous and no one can be empowered.

Because in an autonomous organization, you're only as good as the number of resources you have and the collaboration you have from other teams. So a team could be autonomous, but if they can't get on the payments roadmap, they can't ship anything.

And so what I decided is we are not going to have autonomous leaders. We’re going to be totally integrated. No one’s going to succeed at Airbnb without collaborating with other people.

There’s this age-old truism: “Great leadership is hiring people and giving them operating room and empowering them to do their jobs.” I don’t think that is good leadership at all.

Leadership number one: you have to audit the details. If I’m a CEO, my board empowers me, but they still audit me. How do you know your team is doing a good job if you’re not auditing them? If the board audits you, you should audit the team’s job. And that is, to me, the first expectation of a leader. More importantly, I think there’s another side of the coin. The micromanaging. Because I don’t think anyone wants to be micromanaged. I think of myself as partnering with my executives. I think of it as a creative organization where they’re not autonomous, but they’re in conversation with me. I don’t push decision-making down the organization. I pull decision-making in. I try to pull as many decisions into me as possible, like an orchestra conductor. I try to not have all the ideas or make all the decisions, but be in a constant conversation with my executive team about the decisions.

What I found is that my executives have felt more empowered than when they were more autonomous, because they’re not as much an island. Now they have the resources of the entire company behind them. There are certain personalities who want to do their own thing. They want to be CEOs and don’t want to be in an integrated collaborative organization, and that’s fine. Airbnb and a functional org might not be for them. But the notion that this way of working doesn’t empower people and doesn’t allow them to do as much is not true. Control is not zero sum. There is a scenario where everyone can have more control. There is also a scenario where everyone can be more powerless. I think that’s a very important thing to distinguish.

Side note - Above is Brian Chesky’s view before it was recently bastardized a bit by Paul Graham’s "Founder Mode" post. If interested you can see Brian distancing himself from Paul’s “Founder mode” in this interview with Scott Galloway at 18:16-22:10.

Not every founder-CEO is like Mr. Chesky. In my experience, most founders are less explicit about decision-making culture. They often don't see the specific moments where culture is shaped.

Product managers and department leads understand that decision quality (and buy-in) happens when you get the best decision out of a room. Most founders haven't experienced that at high frequency, so they default to micromanaging.

Yes, a good product hire can have an effect on this. The choice to bring in such a change agent and empower them requires a founder who has overcome their fear of delegation. However, product managers may have more influence than they realize in assisting founders to deal with this fear.

The fear

John Cutler nailed “the fear” in a now deleted tweet.

This fear continues to haunt the founder, even as their startup matures.

It's akin to a mother's perpetual worry for her children's well-being. My mother worried about me when I was a baby. She still worries about me well into adulthood. She’ll never stop. Even though that type of worrying habit is unnecessary now. Well, most of it 😅.

Sometimes founders get so used to obsessing over short term revenue that it becomes their worrying habit. Even when the company is healthy enough for some short term slack.

The quarterly board meetings don’t help the founder in breaking that habit. That’s the root of Elon’s “Funding secured” tweet in 2018 about taking Tesla private.

Same pressures apply to investor boards of non-public companies via end of quarter revenue goals. Below is Elon’s logic for SpaceX from 2013:

Here’s an example of the investor pressure dynamic in a non-public company.

Simon Sinek gets a question from a startup founder. The founder talks about the stressful relationship with his investors. How he's trying to think long term while they pressure him to think short term. Relevant bit is at 01:11:12-01:12:34

Founder: The shareholders are asking me when's my exit plan.

They have a finite game and because they hold the money streams, they think they can control the show. Trying to play a finite game against my infinite game. How do you handle it? Because every time they ask me “what’s your exit plan?”, I kind of say “well, it'll be the coffin and heart attack probably”.

But they don't take that seriously.

How do you handle that.. infinite versus finite players in the same project trying to control the strings?Simon: Do you own the company?

Founder: Yes.

Simon: You took their money?

Founder: Yes.

Simon: {shrugs}

{Audience nod-laughs}

Simon: I got no problem with you looking for investors. But you took the number more than the investor. You took the one who offered you more money (and not) the person who aligned to your values. You took the person who was investing in the exit rather than who was investing in you and your vision.

Berkshire Hathaway does not sell the stocks it buys. Find money from somebody who believes in you and your vision, and will give you the might of their wealth, experience and the people who work there to advise you rather than force you into the exit.Founder: Makes sense. Thanks {nod-laughs}

I felt this investor pressure for the first time when having a 1-on-1 conversation with my CEO. It was a good conversation about long term stuff. But I was too aggressive in pushing for long term thinking. The CEO felt this. He had a more balanced conception of long and short term than I did so he said something very short-term oriented. I told him he’s too focused on short term stuff. To which he said: “Yes Guy, but you can’t forget the short term. You can’t without it.”

To which I said: “Yes, but you can’t without the long term as well”. He smiled in a non-condescending way that conveyed “I already forgot the stuff you’ve yet to learn”. Made me realize I was under-indexing on short term much more than he was under-indexing on long term. I was drinking too much of the product influencers Kool-Aid. The real world is much more nuanced and layered.

Below is an excerpt from an excellent article that details these layers in the most succinct way. (The Two Laws Of Startup Physics by Eric Paley, Ex-CEO/Co-founder of 3M and now a VC managing partner):

Growth is the primary currency of the venture industry. VCs will upsell a startup’s growth to future investors and take a markup on their books. Markups help VCs raise money for their funds and grow their capital base over time. Most VCs want growth so badly that they’ve come to demand it regardless of the cost. This obsession is a short-term optimization with huge long-term implications for the startup, its founders, employees, and, ultimately, investors.

Investors value their startups based on how much money they raise and at what price, rather than thinking clearly about intrinsic value, which has only loose correlation to private valuations.

Entrepreneurs respond to this market demand by spending poorly on activities they know drive vanity metrics that aren’t sustainable to ensure their revenue continues to grow to meet their short-term goal of raising more money.

Many VCs don’t want to spend time engaging these laws of startup physics because they don’t align with the short-term VC incentive structure. Investors often lack the patience and incentives to make wise long-term decisions.

Conveying vision and strategy is hard

Even if the founder manages investor pressure well, there’s still a lot of anxiety around the main task of creating autonomy and a sense of ownership at scale.

That anxiety is dependent on their ability to convey the vision and strategy.

John Cutler writes about this challenge nicely here:

Then there is this this from Shreyas. The expert bias aspect.

Detailing a strategy is not a one-off write up.

Strategy is like culture. It needs to be reiterated via actions, not words on an office poster. It's about consistently making short term decisions that align with a long-term strategy and communicating that continuously.

I remember approaching one of the co-founder’s in my company and telling them that the vision is too high level. That it doesn’t help product managers decide what NOT to prioritize. It doesn’t create company alignment at a productive level. And perhaps one of the co-founders can write a monthly email to the company. An email with their specific thoughts around vision and strategy.

I could see the energy draining out of the co-founder’s body at the thought of writing an email like that. He said that it is generally a good idea, but once you write something, you can’t control how hundreds of people will interpret it. He didn’t trust the team to “get it”.

Thing is, no one knows how to write to hundreds of people. Take Elizabeth Gilberts’ advice (best selling author of “Eat, Pray, Love”). Elizabeth says that she doesn’t know how to write to a demographic. So she writes to herself or to a best friend.

It’s her #1 tip for writing (full list here):

Tell your story TO someone. Pick one person you love or admire or want to connect with, and write the whole thing directly to them —like you're writing a letter. This will bring forth your natural voice. Whatever you do, do NOT write to a demographic. Ugh.

But you are not going to teach the founder how to write. So we are left with the part about trusting the team.

Trust starts with replacing resentment with empathy

The above may be what your CEO/founder is dealing with. Understanding this is important. It helps you replace resentment with empathy towards your leaders. Empathy is your key for building trust.

Product managers' resentment towards leaders is what breeds memes like the three below:

Funny and relatable but not practical.

Even the “practical” product management content out there often fuels resentment towards leadership. Marty Cagan built a consulting company whose total addressable market is based on the premise that most companies do not have truly empowered product teams. I’d argue that the number of companies with truly empowered product teams is close to zero (though, of course, this depends on how you define “truly”).

That’s why this tweet resonates with most product managers:

Resentment could easily turn into contempt. Contempt is the biggest relationship killer (reason #1 in this random clickbait article that pops up when searching for contempt+divorce).

I know I’ve fallen down the resentment hole. I’ve surely unconsciously expressed it to leadership.

Here is how resentment towards leadership could develop in a product manager.

I feel like doing discovery is not valued in this company. All that matters is delivering features, prioritized and handed over from above, with no business prioritization logic or strategy that I can understand. Sometimes it seems like the “strategy” is “do all the things”.

The content interests me and I like my colleagues so I don’t want to leave, but I’m starting to feel like I’m not growing as a PM.

I don’t understand how my work impacts the companies’ goals or what they are.

I want to change the status quo to expand my autonomy in the problem space, but don’t have energy for pushing this change because of the above.

I don’t have the hope that I can change anything as the issue has to do with culture coming from the top.

When will they understand that something has got to give?

Who are these royal “they”?

The PM’s manager and the managers above them?

Sort of. But it’s really 1 or 2 people. The CEO or founders.

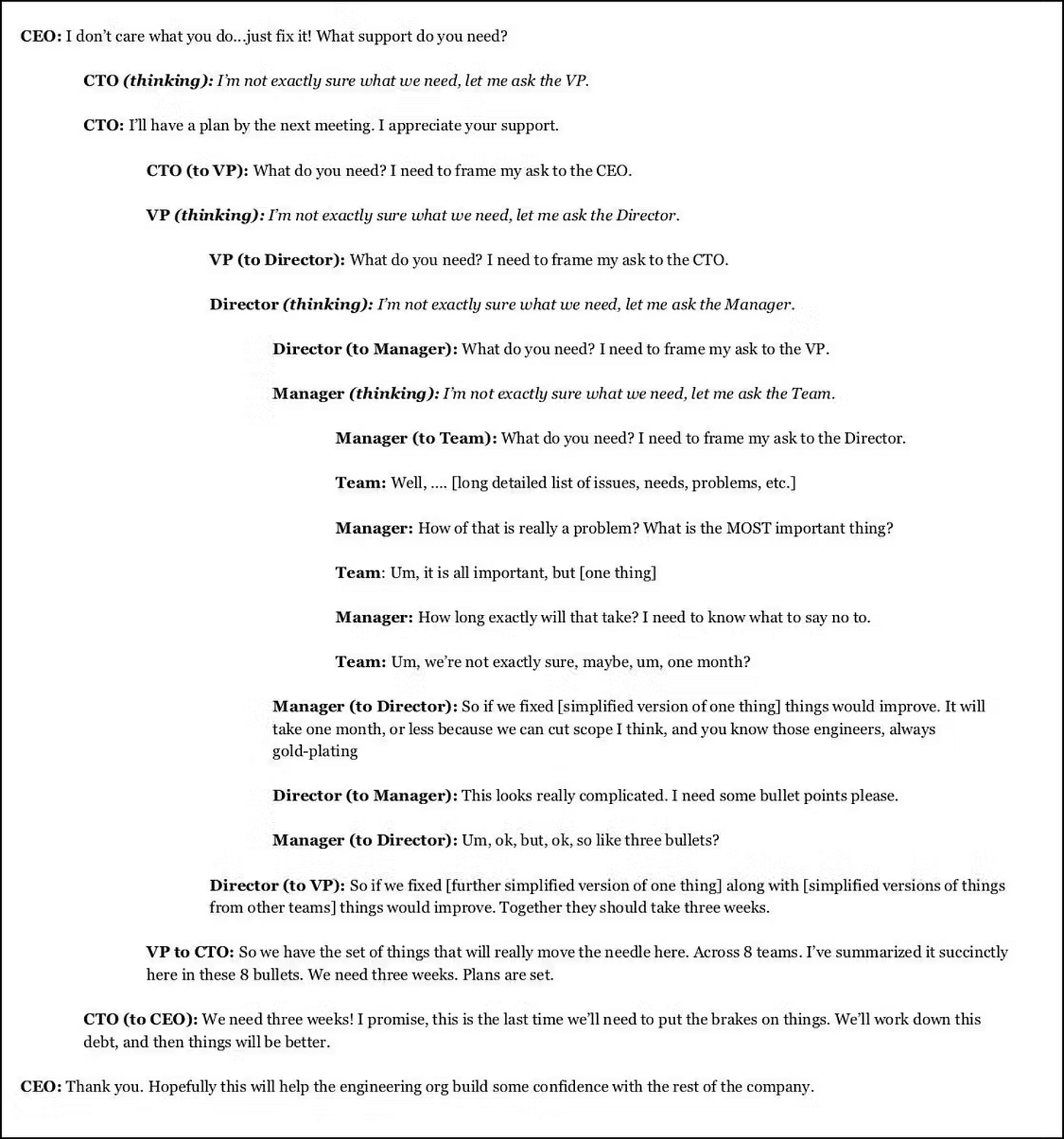

The founder’s message sometimes gets diluted, tapered and misinterpreted as it comes in via the managers.

Some of that message dilution has to do with managers confusing loyalty with agreeableness.

They are afraid that their discovery questions will seem like pushback so they don’t ask for clarity from the people above them, and just become a proxy of a diluted or misinterpreted message.

Loyalty is good but can become an issue if it dominates the culture, often at the cost of autonomy and empowerment.

Esther Perel, a clinical psychologist, has a question for her clients that cuts through this: Were you raised for autonomy, or were you raised for loyalty?

Here’s an excerpt from this written interview with Esther:

If a leader is very “loyalty” oriented they will hire like-minded people.

This creates a specific culture. New hires who are “autonomy” oriented will subconsciously adjust to fit into the “loyalty” culture. Ben Horowitz writes well about this in his book, What You Do Is Who You Are:

Many people believe that cultural elements are purely systematic, that employees only operate within a given corporate culture while they’re in the office. The truth is that what people do at the office, where they spend most of their waking hours, becomes who they are. Office culture is highly infectious. If the CEO has an affair with an employee, there will be many affairs throughout the company. If profanity is rampant, most employees will take that home, too.

So trying to screen for “good people” or screen out “bad people” doesn’t necessarily get you a high-integrity culture. A person may come in with high integrity but have to compromise it to succeed in your environment. Just as Africans in Saint-Domingue became the products of slave culture and then transformed into elite soldiers under Toussaint Louverture, people become the culture they live in and do what they have to do to survive and thrive.

Having said this, I do not believe in “types” of people. Yes, there are people that lean towards autonomy, but that doesn’t mean they can’t be loyal. And when a leader’s fear is triggered then they default to their factory settings as a person. Could be loyalty at the expense of autonomy.

That resentment you are carrying towards the royal “they” as they deprive you of autonomy is legit, but it’s mostly towards a dynamic and probably less so towards a person in the org.

I once worked at a company where the decision-making culture felt like a 9 out of 10 in difficulty. I stayed because I was growing professionally, but it wasn’t easy. What kept me going was this mindset: navigating a 9/10 difficulty now would build the resilience and soft skills I’d need if my next company’s culture was a 6/10.

I treated the experience as a personal growth lab. Whenever frustration arose, I reminded myself, “This is a lab for my personal and professional growth.”

There’s a great quote by Marcus Aurelius that touches on this:

Be tolerant with others and strict with yourself

I also love the way Morgan Housel writes about tolerance for culture difficulties. There’s value in “practicing” to increase that tolerance, whatever level it currently is. Here’s the relevant point from this excellent piece:

The inability to accept hassle, nonsense, and inefficiency frustrates people who can’t accept how the world works.

...If you recognize that BS is ubiquitous, then the question is not “How can I avoid all of it?” but, “What is the optimal amount to put up with so I can still function in a messy and imperfect world?”

If your tolerance is zero – if you are allergic to differences in opinion, personal incentives, emotions, inefficiencies, miscommunication and such – your odds of succeeding in anything that requires other people rounds to zero. You can’t function in the world.

I’ll tell you: So many people don’t have enough tolerance for BS. There’s a gap between their expectations and the reality of how the world works.

Yes. It demands a lot of energy to navigate culture, and it’s easier not to take responsibility. Heck, part of the reason I’m writing this post is for self therapy 😅.

You may be in a place in your career and life where you don’t have energy to go through that type of adversity. But if you do, there is a lot of value in taking on the responsibility.

Jordan Peterson has a great first principal take on resentment and responsibility.

Jordan Peterson is a clinical psychologist. Some of his stuff and ways of conveying messages are very controversial and I realize I’m going to lose some people’s attention when quoting him. I love some of his stuff, but I agree he can sometimes be very aggressive in his ways at the expense of whole demographics, and that recently he has gone off the rails. Below quote is not one of those cases.

Relevant bit is at 00:59:26-01:05:43.

People are often resentful if they see that responsibility has been abdicated. “Why isn't that person doing their job?”

It's like [I want to tell them] “hey man step in. At your workplace. In your family”. And you think, “I shouldn't have to do that extra work”. Well, you shouldn't be a slave. You shouldn't allow yourself to be tyrannized. But if something bugs you, because a responsibility is going unfulfilled, then there's a great opportunity for you.

And this is something I don't think we teach young people well. And one of the things that was so striking about the tour [Jordan did a book tour where he lectured in front of audiences] was that I made a case fairly consistently that most people find the meaning that sustains them through the vicissitudes of life not in happiness but in responsibility. And that would bring everyone to a halt. It would always make the whole theater silent. It's like “oh, I never thought of that connection”. Because maybe you want to avoid responsibility. And you can understand why. You hide from it.

Like one of the biblical stories - Abraham stays in his father's tent until he's 80, and then God gets fed up and tells him to get the hell out and grow up. And everything that he encounters is catastrophic. He encounters tyranny. The Egyptians conspire to steal his wife. He encounters starvation and war. That is what you encounter if you go out in the world. And you think “who the hell wants that? I don't want the responsibility”. It's like well, yes you do. There's nothing better than responsibility.

Now, I say that with some caution. I've been overwhelmed by my apparent responsibility. But I think it's also kept me alive and I mean that literally.

One of the chapters [in my book] is “Be grateful in spite of your suffering”. You need a meaning to sustain you through suffering. And it is the case that you find that meaning in responsibility. And it's good advice for anyone who's at work. You're resentful about this and that, because people aren't pulling their weight.

Pull it!

See what happens.

You'll become indispensable, instantly. You'll know everything. And maybe that job won't be for you, or maybe that relationship won't be for you, but you'll take your hard acquired wisdom and go elsewhere and flourish there.

This kid stopped me in a restaurant one day when I was walking in. He had an undergraduate degree and he was working as a waiter in a chain steak place. He said "about six months ago, I was watching one of your lectures and I decided to stop being resentful about my job”. He was resentful because he had a university degree and is working as a waiter. He said “well I decided I'd start trying at my job. Like really trying as if it was worthwhile”. Said he got three promotions in six months. He's just rocketing up the power hierarchy. Well, it's not power, it's competence. If it's well run then places are full of opportunity.

And that doesn't mean social structures aren't sometimes corrupt. But you can discover that too. If you start to take responsibility and that goes sideways, and you're not being credited with that. Well then that's an indication that you need to restructure the situation. Something's corrupt about it. Or if you can't do that, then you should go somewhere else where that is valued. It's a sign that things aren't right. If you bring your best to the table, and that isn't appreciated then there's something wrong with the table.

I’d go beyond this and say that if you see an opportunity for your growth and for business impact then appreciation can wait.

Yes, lack of appreciation can lead to burnout and the weight of its importance is different per person, and per phase in their lives. But lack of appreciation could be deceiving.

Sometimes, what you think is lack of appreciation is actually a matter of broken communication across hierarchies.

I love this from John Cutler about the telephone game:

First step of taking responsibility is to bypass that broken communication and have a 1-on-1 with the founder/CEO.

Have an open conversation outside of an urgent event.

Ask them what their goals are, and what are the current challenges and friction points preventing them from reaching those goals. More on that type of conversation in another post.

Below is a Tweet thread version of this post. Let’s continue the discussion there 😊

Further resources

High agency by Shreyas:

Office politics by Julie Zhuo:

absolutely brilliant. the shift from resentment to empathy isn’t passive—it’s a high-agency choice. power starts when we take radical responsibility, not just positions.